Russia is a major producer and exporter of oil and natural gas, and its economy largely depends on energy exports. Russia’s economic growth is driven by energy exports, given its high oil and natural gas production. Oil and natural gas revenues accounted for 50% of Russia’s federal budget revenues and 68% of total exports in 2013.

Russia was the world’s largest producer of crude oil including lease condensate and the third-largest producer of petroleum and other liquids (after Saudi Arabia and the United States) in 2014, with average liquids production of 10.9 million barrels per day (b/d). Russia was the second-largest producer of dry natural gas in 2013 (second to the United States), producing 22.1 trillion cubic feet (Tcf).

![energy_consumption]() Russia and Europe are interdependent in terms of energy. Europe is dependent on Russia as a source of supply for both oil and natural gas, with more than 30% of European crude and natural gas supplies coming from Russia in 2014. Russia is dependent on Europe as a market for its oil and natural gas and the revenues those exports generate. In 2014, more than 70% of Russia’s crude exports and almost 90% of Russia’s natural gas exports went to Europe.1

Russia and Europe are interdependent in terms of energy. Europe is dependent on Russia as a source of supply for both oil and natural gas, with more than 30% of European crude and natural gas supplies coming from Russia in 2014. Russia is dependent on Europe as a market for its oil and natural gas and the revenues those exports generate. In 2014, more than 70% of Russia’s crude exports and almost 90% of Russia’s natural gas exports went to Europe.1

Russia is the third-largest generator of nuclear power in the world and fourth-largest in terms of installed nuclear capacity. With nine nuclear reactors currently under construction, Russia is the second country in the world, after China, in terms of number of reactors under construction as of March 2015.2

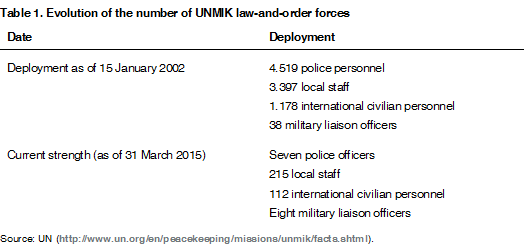

Russia consumed 31.52 quadrillion British thermal units (Btu) of energy in 2012, the majority of which was in the form of natural gas (51%). Petroleum and coal accounted for 22% and 18%, respectively (Figure 1).

Effects of recent sanctions

Sanctions and lower oil prices have reduced foreign investment in Russia’s upstream, especially in Arctic offshore and shale projects, and have made financing projects more difficult.

In response to the actions and policies of the government of Russia with respect to Ukraine, in 2014 the United States imposed a series of progressively tighter sanctions on Russia.3 Among other measures, the sanctions limited Russian firms’ access to U.S. capital markets, specifically targeting four Russian energy companies: Novatek, Rosneft,4 Gazprom Neft, and Transneft. Additionally, sanctions prohibited the export to Russia of goods, services, or technology in support of deepwater, Arctic offshore, or shale projects.5 The European Union imposed sanctions, although they differ in some respects.

In recent years, the Russian government has offered special tax rates or tax holidays to encourage investment in difficult-to-develop resources, such as Arctic offshore and low-permeability reservoirs, including shale reservoirs. Attracted by the tax incentives and the potentially vast resources, many international companies have entered into partnerships with Russian firms to explore Arctic and shale resources. ExxonMobil, Eni, Statoil, and China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) all partnered with Rosneft to explore Arctic fields.6 Despite sanctions, in May 2014, Total agreed to explore shale resources in partnership with LUKoil, but then, because of sanctions, halted its involvement in September. ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, and Statoil also signed agreements with Russian companies to explore shale resources. Virtually all involvement in Artic offshore and shale projects by Western companies has ceased following the sanctions.

Arctic offshore and shale resources are unlikely to be developed without the help of Western oil companies. However, these sanctions will have little effect on Russian production in the short term as these resources were not expected to begin producing for 5 to 10 years at the earliest. The immediate effect of these sanctions has been to halt the large-scale investments that Western firms had planned to make in these resources.

At the same time as the United States and European Union were applying sanctions, oil prices fell by more than half, from an average Brent crude oil price of $108/barrel (b) in March 2014 to just $48/b in January 2015. Both the sanctions and the fall in oil prices have put pressure on the Russian economy in general, and have made it more difficult for Russian energy firms to finance new projects, especially higher-cost projects such as deepwater, Arctic offshore, and shale projects.

Oil

![liquid_fuels_supply_consumption]() Most of Russia’s oil production originates in West Siberia and the Urals-Volga regions. However, production from East Siberia, Russia’s Far East and the Russian Arctic has been growing.

Most of Russia’s oil production originates in West Siberia and the Urals-Volga regions. However, production from East Siberia, Russia’s Far East and the Russian Arctic has been growing.

Russia’s proved oil reserves were 80 billion barrels as of January 2015, according to the Oil and Gas Journal.7 Most of Russia’s reserves are located in West Siberia, between the Ural Mountains and the Central Siberian Plateau, and in the Urals-Volga region, extending into the Caspian Sea.

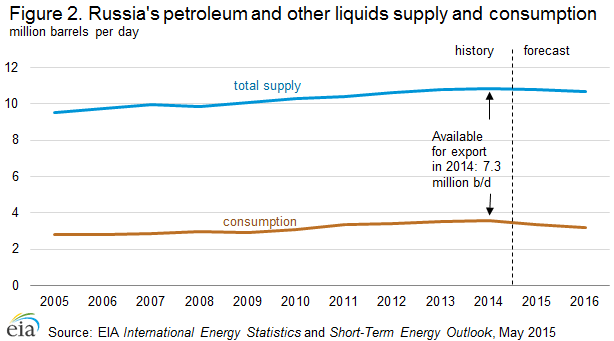

In 2014, Russia produced an estimated 10.9 million b/d of petroleum and other liquids (of which 10.1 million b/d was crude oil including lease condensate), and it consumed slightly more than 3.5 million b/d (Figure 2). Russia exported more than 6 million b/d in 2013, including roughly 5 million b/d of crude oil and the remainder in products. According to EIA’s International Energy Outlook 2014, Russia’s petroleum and other liquids production grows modestly over the long term.

Exploration and production

Most of Russia’s oil production originates in West Siberia and the Urals-Volga regions (Table 1), with about 10% of production in 2013 originating in East Siberia and Russia’s Far East (Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, Yakutia, and Sakhalin). However, this share is up from less than 5% in 2009.8 In the longer term, Russia’s eastern oil fields, along with the untapped oil reserves in the Russian Arctic, may play a larger role. The Russian sector of the Caspian Sea and the undeveloped areas of Timan-Pechora in northern Russia also may hold large hydrocarbon reserves.

A number of new projects are in development. Some of these new projects may only offset declining output from aging fields and not result in significant output growth in the near term. The use of advanced technologies and the application of improved recovery techniques is resulting in increased oil output from some existing oil deposits. Fields in the West Siberian Basin produce the majority of Russia’s oil, with developments at Rosneft’s Samotlor field and Priobskoye area fields extracting more than 1.6 million b/d combined.9

Table 1. Russia’s oil production by region, 2013

| Region |

Thousand b/d |

| Western Siberia |

6,422 |

| Urals-Volga |

2,310 |

| Krasnoyarsk |

426 |

| Sakhalin |

277 |

| Arkhangelsk |

269 |

| Komi Republic |

257 |

| Irkutsk |

227 |

| Yakutiya |

149 |

| North Caucasus |

62 |

| Kaliningrad |

26 |

| Total |

10,425 |

| Source: Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 6 (2014), p. 2. |

Russia’s oil- and natural gas-producing regions

West SiberiaWest Siberia is Russia’s main oil-producing region, accounting for about 6.4 million b/d of liquids production, more than 60% of Russia’s total production in 2013.

10 One of the largest and oldest fields in West Siberia is Samotlor field, which has been producing oil since 1969. Samotlor field has been in decline since reaching a post-Soviet era peak of 635,000 b/d in 2006. However, with continued investment and application of standard enhanced oil recovery techniques, decline at the field has been kept to an average of 5% per year from 2008 to 2014, significantly lower than the natural decline rate for mature West Siberian fields of 10-14% per year.

11

Other large oil fields in the region include Priobskoe, Prirazlomnoe, Mamontovskoe, and Malobalykskoe. While this region is mature, West Siberian production potential is still significant but will depend on improving production economics at fields that are more complex and which contain a significant portion of remaining reserves.

The Bazhenov shale layer, which lies under existing resource deposits, also holds great potential. In the 1980s, the Soviet government tried to stimulate production by detonating small nuclear devices underground. In recent years, the government has used tax breaks to encourage Russian and international oil companies to explore the Bazhenov and other shale reservoirs. However, most shale exploration activities in Russia have been suspended because of sanctions.

Urals-VolgaUrals-Volga was the largest producing region up until the late 1970s when it was surpassed by West Siberia. Today, this region is a distant-second producing region, accounting for about 22% of Russia’s total output. The giant Romashkinskoye field (discovered in 1948) is the largest in the region. It is operated by Tatneft and produced about 300,000 b/d in 2013.12

East SiberiaWith the traditional oil-producing regions in decline, East Siberian fields will be central to continued oil production expansion efforts in Russia. The region’s potential was increased with the inauguration of the Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline in December 2009, which created an outlet for East Siberian oil.

East Siberia has become the center of production growth for Rosneft, the state oil giant. The start-up of the Vankorskoye (Vankor) oil and natural gas field in August 2009 has notably increased production in the region and has been a significant contributor to Russia’s increase in oil production since 2010. Vankor, located north of the Arctic circle, was the largest oil discovery in Russia in 25 years. In 2013, the field produced about 420,000 b/d.13

There are a number of other fields in the region, including the Verkhnechonskoe oil and gas condensate field, the Yurubcheno-Tokhomskoye field, and the Agaleevskoye gas condensate field.14

Yamal Peninsula/Arctic CircleThis region is located in the Yamal-Nenets Autonomous region, and it straddles West Siberia. This region is mostly known for natural gas production. Crude oil development is relatively new for the region. In the near term, the region is facing transportation infrastructure constraints, although the construction of the Purpe-Samotlor pipeline lessened some of these constraints. Transneft also is constructing the Zapolyarye-Purpe pipeline, connecting the Zapolyarye gas and condensate field to the Purpe-Samotlor pipeline.

In addition to the Zapolyarye gas and condensate field, the area is home to the Vostochno Messoyakha and Zapadno Messoyakha, Suzun, Tagul, and Russkoye oil fields, all of which will benefit from the additional transportation capacity. On the Yamal Peninsula itself, gas fields such as Yuzhno Tambey, Severno Tambey, and Khararsavey dominate the landscape, as well as the Vostochno Bovanenkov and Neitin gas and condensate fields.

North CaucasusThe North Caucasus region includes the mature onshore area as well as the promising offshore North Caspian area. LUKoil has been actively exploring some of the deposits situated in the North Caspian and has increased proved reserves in the area by 35% over the past five years. In 2010, Lukoil launched the Yuri Korchagin field, which produced 27,000 b/d in 2013.15 By the end of 2015, Lukoil is scheduled to launch the Filanovsky field that should reach production of 120,000 b/d in 2016. Other discoveries in the area include the Khvalynskoye and Rakushechnoye fields. The development of the region is highly sensitive to taxes and export duties, and any change or cancellation of tax breaks may negatively affect development.

Timan-Pechora and Barents SeaTiman-Pechora and the Barents Sea are located in northwestern Russia. Liquids fields in these areas are relatively small, however there is well-developed oil infrastructure in these areas. Two liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects have been proposed for the area, Gazprom’s Shtokman LNG and Rosneft’s Pechora LNG, both of which have the potential to yield significant quantities of hydrocarbon gas liquids (HGL). However, both projects have been delayed indefinitely.

Sakhalin IslandSakhalin Island is located off Russia’s eastern shore. The offshore area to the east of Sakhalin Island is home to a number of large oil and natural gas fields with significant investment by international companies. Much of Sakhalin’s resources are being developed under two production-sharing agreements (PSA) signed in the mid-1990s. The Sakhalin-1 PSA is operated by ExxonMobil, which holds a 30% stake. Other members of the PSA include Rosneft (through two subsidiaries), Indian state-owned oil company ONGC Videsh, and a consortium of Japanese companies.16 The Sakhalin-1 PSA covers three oil and gas fields: Chayvo, Oduptu, and Arkutun-Dagi. Production started at Chayvo field in 2005, at Oduptu field in 2010, and at Arkutun-Dagi field in January 2015.17 Sakhalin-1 mainly produces crude oil and other liquids, most of which are exported via the De-Kastri oil terminal. Most of the natural gas currently produced at Sakhalin-1 is reinjected with small volumes of gas sold domestically.

The Sakhalin-2 PSA covers two major fields, the Piltun-Astokhskoye oil field and the Lunskoye gas field, and it includes twin oil and gas pipelines running from the north of the island to the south end of the island where the consortium has an oil export terminal and an LNG liquefaction and export terminal. The Sakhalin-2 consortium members include Gazprom which owns 50% plus one share, Shell with 27.5%, Mitsui with 12.5%, and Mitsubishi with 10%.18 When the PSA was originally signed, the consortium did not include any Russian companies and, compared with most PSAs, the terms were heavily weighted in favor of the interests of the consortium over the interests of the government. Sakhalin-2 produced its first oil in 1999 and first LNG in 2009. The project incurred significant cost overruns and delays, and these were part of the justification the Russian government used to force Shell, which at the time owned a 55% interest in Sakhalin-2, and the other consortium members to sell a controlling interest in the consortium to Gazprom.19

Russia’s oil grades

Russia has several oil grades, including Russia’s main export grade, Urals blend. Urals blend is a mix of heavy sour crudes from the Urals-Volga region and light sweet crudes from West Siberia. The mixture and thus the quality can vary, but Urals blend is generally a medium gravity sour crude blend and, as such, is generally priced at a discount to Brent crude. Siberian Light crude is a higher quality and thus more valuable when marketed on its own, but it is usually blended into Urals crude because there is limited infrastructure to move it to market separately.20

Sokol grade is produced by the Sakhalin-1 project and is a light, sweet crude with an API gravity of 36.9° and 0.27% sulfur content.21 As of December 2014, Vityaz blend is being replaced with a new grade of crude, Sakhalin blend. Vityaz was a light (33.6°API), sweet (0.24% sulfur content), crude produced under the Sakhalin-2 production-sharing agreement (PSA) at Piltun and Astokh fields. Sakhalin blend adds to this condensate production from the Kirinskoye gas and condensate field. Since its introduction, Sakhalin blend has traded at a premium to Vityaz blend. Like the Vityaz crude, Sakhalin blend is loaded at the Prigorodnoye port, on the southern tip of Sakhalin Island.22

The Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean (ESPO) blend came on stream in late 2009 and is a mix of crudes produced in several Siberian fields. The grade is exported through the recently constructed ESPO Pipeline to China as well as through Russia’s Pacific coast port of Kozmino to other Asian countries. ESPO blend is a fairly sweet, medium-light blend, with a gravity of 35.7°API and 0.48% sulfur content.23

Sector organization

Most of Russia’s oil production remains dominated by domestic firms (Table 2).24 Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia initially privatized its oil industry, but Russia’s oil and gas sector has gradually reverted to state control over the past few years.

Starting in the late 1990s, privately-owned companies drove growth in the sector, and a number of international oil companies attempted to enter the Russian market, with varying success. More recently the Russian oil industry has consolidated into fewer firms with more state control. Five firms, including their shares of joint venture production, account for more than 75% of total Russian oil production, and the Russian state directly controls more than 50% of Russian oil production. Smaller firms have generally had higher production growth than larger firms, but smaller firms could be less resilient in the face of lower oil prices.25

In 2003, BP invested in TNK, forming TNK-BP, a 50-50 joint venture and one of country’s major oil producers. However, in 2012 and 2013, the TNK-BP partnership was dissolved, and the state-controlled Rosneft acquired nearly all of TNK-BP’s assets. For its share in TNK-BP, BP received cash and 18.5% of Rosneft.26 In the previous decade, Rosneft emerged as Russia’s top oil producer following the liquidation of Yukos assets, which Rosneft acquired.

A number of ministries are involved in the oil sector. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment issues field licenses, monitors compliance with license agreements, and levies fines for violations of environmental regulations. The Ministry of Energy develops and implements general energy policy. The Ministry of Economic Development supervises tariffs, while the Finance Ministry is responsible for hydrocarbon taxes.27

There are two main hydrocarbon taxes in Russia, the minerals extraction tax and the export tax. The export tax varies for crude oil and for different products, and in 2011 product export taxes were changed so that export tax rates on all products were lower than for crude oil in order to encourage investment in refining capacity. In recent years, the government has also offered special tax rates or tax holidays for difficult-to-develop resources, such as Arctic offshore and low-permeability reservoirs, including shale reservoirs. On January 1, 2015, hydrocarbon tax rates changed again. Previously, the export tax was about twice as high as the extraction tax. The 2015 tax change raised the extraction tax and lowered the export tax. This change will increase the value of previously agreed discounts to the extraction tax for difficult resources, and it will also tend to increase exports of crude oil over exports of refined products.28

Table 2. Russia’s oil production by company, 2013

| Company |

Thousand b/d |

| Rosneft |

3,997 |

| Lukoil |

1,703 |

| Surgutneftegaz |

1,224 |

| Gazprom Neft |

640 |

| Tatneft |

526 |

| Gazprom |

340 |

| Slavneft |

335 |

| Bashneft |

320 |

| Russneft |

316 |

| PSA operators |

278 |

| Novatek |

95 |

| Others |

651 |

| Total |

10,425 |

| Source: Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 7 (2014), pp. 3-5. |

Refinery sector

Russia has 40 oil refineries with a total crude oil distillation capacity of 5.5 million b/d as of January 1, 2015, according to Oil and Gas Journal.29 Rosneft, the largest refinery operator, owns nine major refineries in Russia.30 LUKoil is the second-largest operator of refineries in Russia with four major refineries.31 Many of Russia’s refineries are older, simple refineries, with low-quality fuel oil accounting for a large share of their output. Previous tax changes have, with modest success, encouraged companies to invest in upgrading refineries to produce more high-value products such as diesel and gasoline. The tax changes introduced in 2015 will negatively affect the refineries that have yet to be upgraded.32

Oil exports

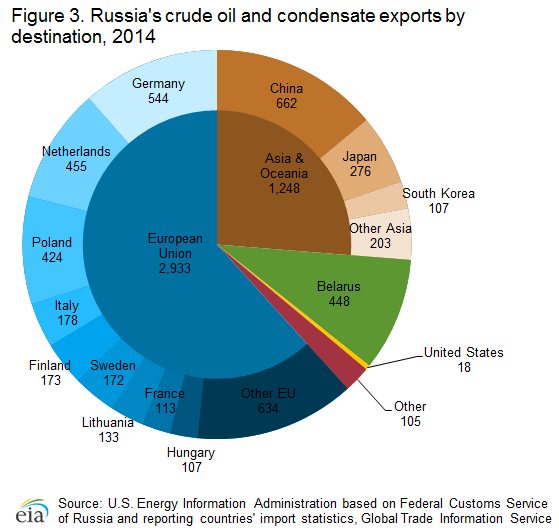

In 2014, Russia had roughly 7.3 million b/d of petroleum and other liquids available for exports. The vast majority of Russian crude exports (72%) went to European countries, particularly Germany, Netherlands, Belarus, and Poland (Figure 3).33 Revenues from crude oil and products exports in 2013 accounted for 54% of Russia’s total export revenues. Additionally, half of Russia’s federal budget revenue in 2013 came from mineral extraction taxes and export customs duties on oil and natural gas. While Russia is dependent on European consumption, Europe is similarly dependent on Russian oil supply, with more than 30% of European crude oil supplies in 2014 coming from Russia.34

Asia accounted for 26% of Russian crude exports in 2014, with China and Japan accounting for a growing share of total Russian exports.35 Russia’s crude oil exports to North America and South America have been largely displaced by increases in crude oil production in the United States, Canada, and, to a lesser extent, in Brazil, Colombia, and other countries in the Americas. Russia’s Transneft holds a near-monopoly over Russia’s pipeline network, and the vast majority of Russia’s crude oil exports must traverse Transneft’s system to reach bordering countries or to reach Russian ports for export. Smaller volumes of exports are shipped via rail and on vessels that load at independently-owned terminals.

Russia also exports fairly sizeable volumes of oil products. According to Eastern Bloc Research, Russia exported about 1.5 million b/d of fuel oil and an additional 860,000 b/d of diesel in 2013. It exported smaller volumes of gasoline (100,000 b/d) and liquefied petroleum gas (60,000 b/d) during the same year.36![crude_oil_export]()

Pipelines

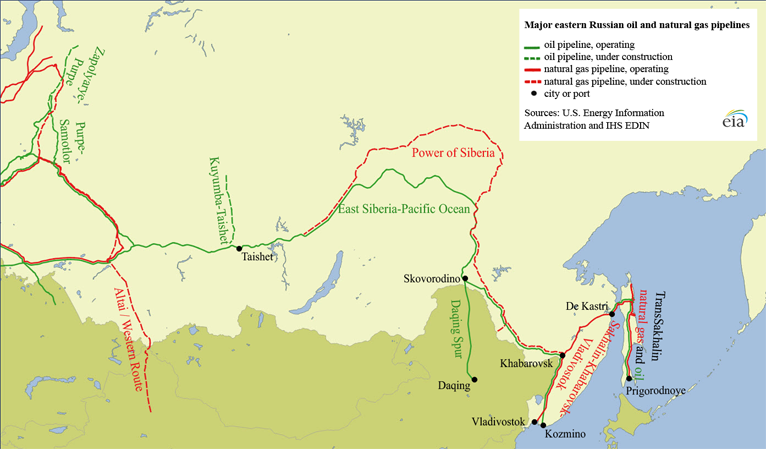

Russia has an extensive domestic distribution and export pipeline network (Table 3).37 Russia’s domestic and export pipeline network is nearly completely owned and run by the state-run Transneft. One notable exception is the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) pipeline, which runs from Tengiz field in Kazakhstan to the Russian Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. The CPC pipeline is owned by a consortium of companies with the largest share (24%) owned by the Russian government, whose interests in the consortium are represented by Transneft. KazMunaiGaz (19%), the state-owned oil and natural gas company of Kazakhstan, and Chevron (15%) are the second- and third-largest shareholders in the consortium. Another exception is the TransSakhalin pipeline, owned by the Sakhalin-2 consortium, in eastern Russia (Figure 4).

Table 3. Russia’s major crude oil pipelines

| Facility |

Status |

Capacity (million b/d) |

Total length (miles) |

Supply regions |

Destination |

Details |

| Western pipelines |

| Druzhba |

operating |

2 |

2,500 |

West Siberia and Urals-Volga regions |

Europe |

completed in 1964 |

| Baltic Pipeline System 1 |

operating |

1.3 |

730 |

connects to Druzhba |

Primorsk Port on the Gulf of Finland |

completed in 2001 |

| Baltic Pipeline System 2 |

operating |

0.6 |

620 |

connects to Druzhba |

Ust-Luga Port on the Gulf of Finland |

completed in 2012 |

| North-West Pipeline System |

inactive |

0.3 |

50 |

connects to Druzhba |

Butinge, Lithuania and Ventspils, Latvia on the Baltic Sea |

inactive since 2006 |

| Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC) |

operating |

0.7 |

940 |

Tengiz field, Kazakhstan |

Novorossiysk, Russia on the Black Sea |

Planned expansion to 1.3 million b/d by 2016 |

| Baku-Novorossiysk Pipeline |

operating |

0.1 |

830 |

Caspian and central Asia, via Sangachal Port, Azerbaijan on the Caspian Sea |

Novorossiysk, Russia on the Black Sea |

completed in 1996 |

| Eastern pipelines |

| TransSakhalin |

operating |

0.2 |

500 |

Sakhalin fields (offshore northern Sakhalin) |

Pacific seaport of Prigorodnoye (Southern Sakhalin Island) |

completed in 2008 |

Eastern Siberia-Pacific Ocean

(ESPO) Pipeline |

operating |

ESPO-1 – 1.2 currently,

1.6 by 2020

ESPO-2 – 0.5 currently,

1.0 by 2020

China spur – 0.3 currently,

0.6 by 2018 |

ESPO-1 – 1,700

ESPO-2 – 1,300

Daqing spur – 660 |

East Siberian fields and, via connecting

pipelines, West

Siberian fields and Yamal-Nenets region |

Pacific seaport of Kozmino with a spur to Daqing, China |

ESPO-1 (Taishet-Skovorodino) completed in 2009

ESPO-2 (Skovorodino-Kozmino) completed in 2012 Skovorodino-Daqing, China spur completed in 2010 |

| Purpe-Samotlor Pipeline |

operating |

0.5 |

270 |

Yamal-Nenets and Ob Basins |

connects to ESPO Pipeline |

completed in 2011 |

| Zapolyarye-Purpe Pipeline |

construction |

0.6 (expandable to 0.9) |

300 |

Zapolyarye and Yamal-Nenets region |

connects to Purpe-Samotlor and ESPO pipelines |

Planned for 2016 may be delayed 2-3 years or may carry minimal volumes (30,000 b/d) as field completions have been delayed |

| Kuyumba-Taishet |

construction |

0.16 |

430 |

Kuyumba field (start- up delayed until 2018) |

connects to ESPO Pipeline |

Planned for 2016, may be delayed or may carry minimal volumes as field completions have been delayed |

| Source: U. S. Energy Information Administration based on Transneft, Sakhalin Energy, Caspian Pipeline Consortium, State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic, Orlen Lietuva, European Parliament, Nefte Compass, and Platt’s Oilgram Price Report. |

Figure 4. Major eastern Russian oil and natural gas pipelines![eastern_map]()

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration and IHS EDIN

Ports

There are at least 20 ports serving as export outlets for Russian hydrocarbons to various markets, including Europe, the Americas, and Asia. Four of these ports together accounted for 85% of Russia’s seaborne crude exports in 2014 (Table 4).38

The Primorsk and Ust-Luga terminals are both located near St. Petersburg, Russia, on the Gulf of Finland. The Primorsk terminal opened in 2006 and has a loading capacity of more than 1.2 million b/d.39 The Ust-Luga oil terminal opened in 2009 and has a loading capacity of more than 0.5 million b/d.40 Both Primorsk and Ust-Luga receive oil from the Baltic Pipeline System, which brings crude from fields in the Timano-Pechero, West Siberia, and Urals-Volga regions. Ust-Luga is also a major port for Russian coal and HGL exports.

Novorossiysk is Russia’s main oil terminal on the Black Sea coast. Its load capacity is more than 1 million b/d.41

Kozmino is located near the city of Vladivostok, in Russia’s far eastern Primorsky province and is the terminus of the ESPO crude oil pipeline. The port opened in December 2009 with an initial capacity of 0.3 million b/d. Kozmino initially received crude oil by rail from Skovorodino until the second phase of the ESPO pipeline opened in 2012.42 In 2015, almost 0.6 million b/d is expected to be exported through Kozmino port, slightly below the current capacity.43

Table 4. Russia’s crude exports by port, 2014

| Port |

Thousand b/d |

| Novorossiysk |

1,332 |

| Primorsk |

815 |

| Ust-Luga |

556 |

| Kozmino |

487 |

| De Kastri |

161 |

| Prigorodnoye |

112 |

| Varandey |

101 |

| Others |

172 |

| Total |

3,737 |

| Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration based on Lloyd’s List Intelligence (APEX tanker data) |

Hydrocarbon gas liquids

Russian output of hydrocarbon gas liquids (HGL) is expected to grow over the coming years. HGL refers to both the natural gas liquids (paraffins or alkanes such as ethane, propane, and butanes) and olefins (alkenes) produced by natural gas processing plants, fractionators, crude oil refineries, and condensate splitters. HGL is produced in association with both natural gas and petroleum fuels.

Changes in Russia’s export tax regime have spurred investment in refining capacity to produce higher quantities of gasoline and lighter distillates, in lieu of the high share of heavier fuel oil and gasoil the country’s refiners previously exported. The increasing use of catalytic and hydrocracking units is expected to result in increased HGL production at refineries. Further boost to HGL supply will come from natural gas processing, as Russian natural gas producers develop richer natural gas resources and as more associated gas production (which is currently flared) is connected to gas processing plants.

With a surplus of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG)–a mixture of propane and butane–on the Russian market, major producers have targeted the export market along with the development of HGL-fed petrochemical capacity as outlets for their growing production. Traditionally, the main outlet for Russian LPG exports had been shipments to Europe by rail. In mid-2012, Russia’s first modern LPG export terminal came online in Taman on the Black Sea. With a design capacity of approximately 30,000 barrels per day (b/d) of pressurized cargo,44 the port handled on average just under 7,000 b/d in the first nine months of 2014,45 all brought in by rail. In mid-2013, Sibur, Russia’s largest LPG producer, shipped its first LPG cargo out of Ust-Luga, outside St. Petersburg.46 In a first for Russia, the terminal is also capable of handling both pressurized and refrigerated product, with a combined capacity of nearly 50,000 b/d. The Ust-Luga terminal, like Taman, is capable of receiving LPG by rail. Additional volumes of LPG are produced on-site at the Novatek-operated Gas Condensate Fractionation and Transshipment Complex.47

In addition to direct exports, Russian companies are seeking to use domestically produced LPG in petrochemical manufacturing, thus capturing more of the value and minimizing their export tariff exposure. In December 2014, Sibur commissioned its propane dehydrogenation (PDH) facility at the Tobolsk-Polymer complex in West Siberia,48 which is capable of producing 510,000 tons per year of polymer-grade propylene from an estimated 33,000 barrels per day of propane feedstock. The company is planning to further increase its liquids consumption at the Tobolsk site with a proposed 1.5 million ton per year ethylene cracker.49 While some of the feedstock for the plant will consist of ethane, the plant is expected to consume primarily propane and butane to manufacture ethylene, propylene, and butylene/butadiene that will then feed into the production of derivative products, including high- and low-density polyethylene and polypropylene.

Natural gas

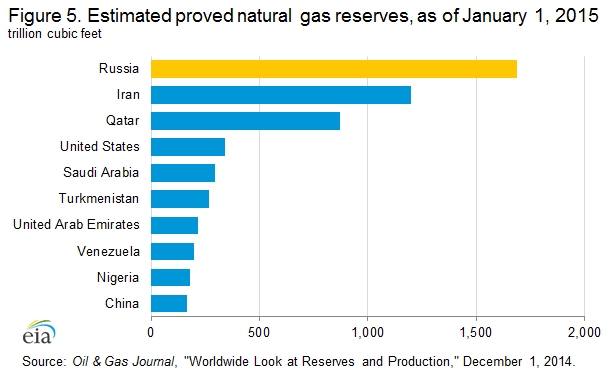

Russia holds the largest natural gas reserves in the world, and is the second-largest producer of dry natural gas. The state-run Gazprom dominates Russia’s upstream natural gas sector, although production from other companies has been growing.

According to Oil and Gas Journal, Russia held the world’s largest natural gas reserves, with 1,688 trillion cubic feet (Tcf), as of January 1, 2015 (Figure 5).50 Russia’s reserves account for about a quarter of the world’s total proved reserves. The majority of these reserves are located in West Siberia, with the Yamburg, Urengoy, and Medvezhye fields accounting for a significant share of Russia’s total natural gas reserves.![natural_gas_reserves]()

Sector organization

The state-run Gazprom dominates Russia’s upstream natural gas sector, producing 73% of Russia’s total natural gas output in 2013 (Table 5).51 While independent and oil company producers have gained importance, with producers such as Novatek and LUKoil contributing increasing volumes to Russia’s production in recent years, upstream opportunities remain fairly limited for independent producers and other companies, including Russian oil majors. Furthermore, Gazprom’s dominant upstream position is reinforced by its legal monopoly on pipeline gas exports.

Much like the oil sector, a number of ministries and regulatory agencies are involved in the natural gas sector. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment issues field licenses, monitors compliance with license agreements, and levies fines for violations of environmental regulations. The Ministry of Energy develops and implements general energy policy and is also charged with overseeing LNG exports. The Finance Ministry is responsible for hydrocarbon extraction and export taxes, while the Ministry of Economic Development supervises tariffs.52

The main regulatory agencies involved in the sector include the Federal Tariff Service (regulates pipeline tariffs) and the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (oversees charges of abuse of market dominance, including charges related to third-party access to pipelines).

Table 5. Russia’s natural gas production by company, 2013

| Company |

Bcf/d |

| Gazprom |

47.2 |

| Novatek |

6.0 |

| Rosneft |

2.6 |

| LUKoil |

2.0 |

| Surgutneftegaz |

1.2 |

| ITERA |

1.2 |

| PSA operators |

2.7 |

| Others |

1.8 |

| Total |

64.6 |

| Source: Source: Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 34, p. 14. |

Exploration and production

The bulk of the country’s natural gas reserves under development and production are in northern West Siberia (Table 6).53 However, Gazprom and others are increasingly investing in new regions, such as the Yamal Peninsula, Eastern Siberia, and Sakhalin Island, to bring gas deposits in these areas into production. Some of the most prolific fields in Siberia include Yamburg, Urengoy, and Medvezhye, all of which are licensed to Gazprom. These three fields have seen output declines in recent years.

In 2013, Russia was the world’s second-largest dry natural gas producer (22.1 Tcf), surpassed only by the United States (24.3 Tcf). Independent gas producers such as Novatek have been increasing their production rates, with non-Gazprom sources expected to continue to increase in the future. Higher production rates have resulted from a growing number of companies entering the sector, including oil companies looking to develop their gas reserves. Russian government efforts to decrease the widespread practice of natural gas flaring and to enforce gas utilization requirements for oil extraction may result in additional increases in production.

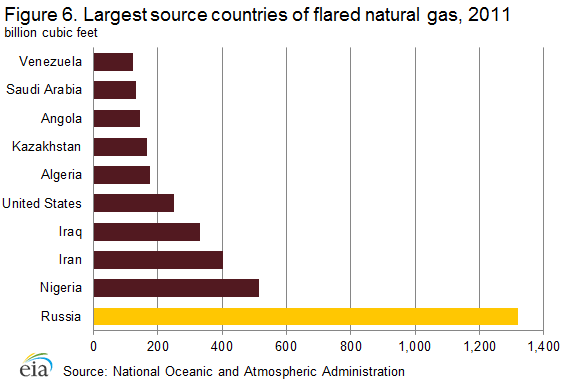

Gas flaringIn Russia, natural gas associated with oil production is often flared. According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Russia flared an estimated 1,320 Bcf of natural gas in 2011, the most of any country. At this level, Russia accounted for about 27% of the total volume of gas flared globally in 2011 (Figure 6).54 A number of Russian government initiatives and policies have set targets to reduce routine flaring of associated gas. Also, regulatory changes have made it easier and more profitable for third-party producers to transport and market their natural gas. However, little progress has been made to reduce routine gas flaring in Russia.

Table 6. Russia’s natural gas production by region, 2013

| Region |

Bcf/d |

| West Siberia |

57.7 |

| Yamalo-Nenets |

53.7 |

| Khanti-Mansiisk |

3.5 |

| Tomsk |

0.5 |

| East Siberia and the Far East |

3.4 |

| Sakhalin |

2.7 |

| Irkutsk |

0.3 |

| Krasnoyarsk |

0.3 |

| Yakutsk |

0.2 |

| Urals-Volga |

3.1 |

| Orenburg |

1.5 |

| Astrakhan |

1.0 |

| Others |

0.7 |

| Komi Republic |

0.3 |

| North Caucasus |

0.1 |

| Total |

64.6 |

| Source: Source: Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 34, p. 14. |

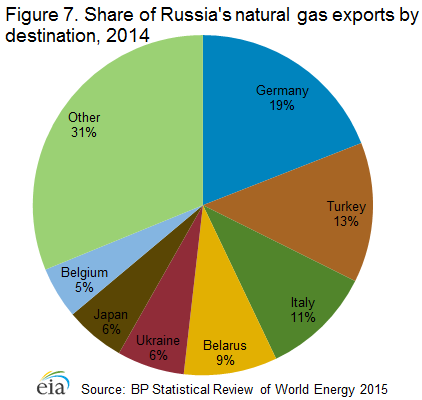

Natural gas exports

In 2014, almost 90% of Russia’s 7.1 Tcf of natural gas exports were delivered to customers in Europe via pipeline, with Germany, Turkey, Italy, Belarus, and Ukraine receiving the bulk of these volumes (Figure 7).55 Much of the remainder was delivered to Asia as LNG. Ukraine’s imports of Russian natural gas in 2014 were about half the level in 2013, when Ukraine was the third-largest importer of Russian natural gas. Because of a pricing and payments dispute and as part of the wider tensions between the two countries, Ukraine did not buy natural gas from Russia during most of the second half of 2014.

Revenues from natural gas exports in 2013 accounted for about 14% of Russia’s total export revenues. While not as large as Russia’s export earnings from crude oil and other liquids, Russia still has a significant level of dependence on Europe as a market for its gas. Europe is, likewise, dependent on Russia for its supply of natural gas. In 2013, Europe received about 30% of its natural gas from Russia, with about half of that volume delivered via Ukraine. Additionally, some countries within Europe, especially Finland, the Baltics, and much of Southeast Europe, receive almost all of their natural gas from Russia.

Since the mid-2000s, Western European natural gas consumption has generally been flat to declining, prompting Russia to look to Asia and LNG as a means to diversify its natural gas exports. U.S. and European Union (EU) sanctions, implemented in 2014, accelerated Russia’s pivot to the east, with Russia signing two pipeline deals with China in 2014 covering exports that could eventually reach 2.4 Tcf per year.![natural_gas_exports]()

Pipelines

In 2013, Russia’s natural gas transportation system included more than 100,000 miles of high-pressure pipelines and 26 underground natural gas storage facilities.56 Most of Russia’s natural gas pipelines were built during the Soviet era, and about 75% of the system is more than 20 years old. Since the late 2000s, Gazprom has been adding major new pipelines to accommodate new sources of supply, including fields in Yamal and Eastern Siberia, and new export routes, including exports to China and new pipelines to Europe that avoid Ukraine.

The Unified Gas Supply (UGS) system is the collective name for the interconnected western portion of Russia’s natural gas pipelines (Table 7).57 The UGS system includes domestic pipelines and the domestic portion of export pipelines in European Russia, but it does not include pipelines in eastern Russia. In 2007, the Russian government directed Gazprom to establish an Eastern Gas Program (EGP) to expand gas infrastructure in eastern Siberia and Russia’s Far East. The backbone of the EGP is the Power of Siberia pipeline, which is currently under construction.

Table 7. Russia’s major natural gas pipelines

| Facility |

Status |

Capacity (trillion cubic feet per year) |

Total length (miles) |

Supply regions |

Markets |

Details |

| Western pipelines |

| Yamal-Europe |

operating |

1.2 |

more than 1,000 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Poland, Germany, and northern Europe via Belarus |

|

| Blue stream |

operating |

0.6 |

750 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Turkey via the Black Sea |

Started operations in 2003 |

| Nord stream |

operating |

1.9 |

760 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Germany and northern Europe via the Baltic Sea |

Started operations in 2011 |

| Urengoy-Ukhta, Bovanenkovo-Ukhta, and Ukhta-Torzhok |

operating and under construction |

up to 6.0 |

more than 1,500 |

Bovanenkovo field on the Yamal peninsula and Urengoy area fields |

Western Russia and Europe |

The Urengoy-Ukhta-Torzhok line started operations in 2006. The 1st Bovanenkovo-Ukhta line started operations in 2012. |

| Soyuz and Brotherhood (Urengoy-Pomary-Uzhgorod) |

operating |

more than 3.5 |

more than 2,800 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area, Russian Urals fields, and Central Asia |

Western Russia and Europe via Ukraine |

First major natural gas export lines to Europe, built and brought online during the Soviet era. |

| Southern Corridor pipelines |

construction |

2.2 |

Western route – 550 Eastern route – 1,010 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Turkey and Europe via Turkish stream pipeline |

Construction on the Western route began in 2012 |

| Turkish stream – line 1 |

planning |

0.6 |

more than 500 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Turkey |

Announced completion by end of 2016 |

| Turkish stream – lines 2-4 |

planning |

1.7 |

more than 500 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Southeast Europe via Turkey |

By 2019 |

| South stream |

canceled |

2.2 |

560 (offshore) |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

Southeast Europe via the Black Sea |

Canceled in late 2014 and replaced with Turkish stream |

| Eastern pipelines |

| TransSakhalin |

operating |

0.3 |

500 |

Sakhalin fields (offshore northern Sakhalin) |

Sakhalin LNG plant, Prigorodnoye, southern Sakhalin Island |

Started operations in 2008 |

| Sakhalin-Khabarovsk-Vladivostok |

operating |

0.2 |

1,120 |

Sakhalin fields (offshore northern Sakhalin) |

Eastern Russia with potential exports to Asia via proposed Vladivostok LNG or new pipelines |

Started operations in 2011. Expandable to 1.1 Tcf per year with additional compression. |

| Power of Siberia, phase 1 (“Eastern route” for exports to China) |

construction |

1.3 |

1,370 |

Chayodinsk field, Yakutia region, East Siberia |

Eastern Russia and northeast China |

Announced start of late 2017 |

| Power of Siberia (complete route) |

construction |

2.2 |

2,490 |

East Siberian fields including Chayodinsk in Yakutia region and Kovytka in Irkutsk region |

Eastern Russia and northeast China, with potential additional exports to Asia via proposed Vladivostok LNG or new pipelines |

2019 or later |

| Altai/Western route |

planning |

1.1 |

1,620 |

West Siberian fields including Urengoy area |

China |

2020 or later |

| Source: U. S. Energy Information Administration based on Gazprom, GazpromExport, Sakhalin Energy, World Gas Intelligence, Nefte Compass, RT, and Reuters. |

Third-party access to pipelines

Gazprom is sole owner of virtually all of Russia’s natural gas pipelines. Russia’s 1999 Law on Gas Supply requires owners of all gas systems to provide non-discriminatory access to any available capacity with the aim of supplying domestic consumers. Separate regulations established rules for third-party access to the UGS system, but no rules have been established for access to pipelines that are not part of the UGS system. Access to pipeline capacity for exports is not included, as the 2006 Law on Gas Exports grants pipeline export rights exclusively to the owner of the UGS system, which is Gazprom.58

Despite these long-standing laws, independent natural gas producers, including state-owned oil companies, have only recently begun to get access to some of Gazprom’s domestic pipelines. Actions by the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (FAS) have helped promote better third-party access. Between 2008 and 2011, the FAS brought 28 infringement cases against Gazprom related to third-party access. Third-party gas transported by Gazprom grew from 10% of total UGS system throughput in 2009 to almost 17% in 2013.59 The FAS has also proposed new laws that would fix many of the deficiencies in the current laws and regulations, including the current lack of regulations for third-party access to pipelines that are not part of the UGS system. Many of the recent disputes over pipeline access have been related to eastern gas pipelines, which are not part of the UGS system.

In order to monetize its Sakhalin-1 natural gas resources, Rosneft has proposed to build a Far East LNG export facility at the southern end of Sakhalin Island. However, this proposal depends on Rosneft being able to send its gas through the Gazprom-controlled TransSakhalin natural gas pipeline. Gazprom has repeatedly denied Rosneft access to the pipeline on grounds that there is no available capacity, because Gazprom needs all the capacity to feed its existing Sakhalin-2 LNG plant and the LNG expansion it plans to build. Gazprom, incidentally, would like to buy gas from the Sakhalin-1 project to use as supply for its LNG expansion. Rosneft filed a court case to try to force Gazprom to give it pipeline access, but the court ruled against Rosneft in February 2015. The matter is still under investigation by the FAS, but the Russian government’s Audit Chamber has criticized Rosneft’s LNG proposal as being more costly than Gazprom’s LNG expansion plans.60

Liquefied natural gas

Russia has a single operating liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility, Sakhalin LNG, which has been operating since 2009 with an original design capacity of 9.6 million tons (mt) of LNG per year (approximately 460 Bcf of natural gas). The majority of the LNG has been contracted to Japanese and South Korean buyers under long-term supply agreements. Debottlenecking and optimization of the facility added up to 3.2 mt (150 Bcf) of capacity in 2011,61 with much of the additional LNG sold under shorter-term agreements or on spot markets. In 2014, Sakhalin LNG exported slightly more than 500 Bcf of gas, which went to Japan (79%), South Korea (18%), China (1%), Taiwan (1%), and Thailand (1%).62

In 2013, Russia modified it Law on Gas Exports to allow Novatek and Rosneft to export LNG, breaking Gazprom’s monopoly on all gas exports. There are a number of proposals in various stages of planning for new LNG terminals in Russia, including a second LNG liquefaction facility that is under construction (Table 8).63 Yamal LNG, which began construction in 2013, is owned by a consortium, led by Novatek with a 60% interest, and joined by Total and CNPC with 20% each. The first of three liquefaction trains is scheduled to be online by 2017. The three trains will each have a capacity of 5.5 mt of LNG per year, and they will draw gas from the South Tambeyskoye natural gas and condensate field located in the northeast of the Yamal Peninsula.64

To transport LNG from its arctic location, Yamal LNG has commissioned the construction of up to 16 ice-class tankers. Exports are mainly aimed at Asian LNG markets, and during most of the year, the ice-class tankers will take cargoes west from the Yamal peninsula directly to Asia, transiting the Arctic Ocean and the Bering Strait. In winter, when the direct route is too ice-bound to be navigable, the ice-class tankers will take cargoes west from the Yamal peninsula to Europe. In Europe the LNG will be loaded on to regular LNG tankers that will deliver the cargoes to Asia via the Suez Canal.

Table 8. Russia’s Liquefied natural gas pipelines

| Facility |

Area |

Status |

Capacity (million metric tons of LNG per year) |

Announced start year |

Owners |

| Liquefaction projects |

| Sakhalin LNG |

Pacific coast |

operating |

9.6 |

2009 |

Gazprom, Shell, Mitsui, and Mitsubishi |

| Yamal LNG |

Arctic coast |

construction |

16.5 |

2017 |

Novatek, Total, and CNPC |

| Baltic LNG |

Baltic coast |

planning |

10 |

2018 |

Gazprom |

| Vladivostok LNG |

Pacific coast |

planning |

15 |

2018 |

Gazprom |

| Sakhalin LNG (expansion) |

Pacific coast |

planning |

5 |

post 2018 |

Gazprom, Shell, Mitsui, and Mitsubishi |

| Far East LNG |

Pacific coast |

planning |

5 |

2018-19 |

ExxonMobil, Rosneft, ONGC Videsh, and SODECO, a Japanese consortium |

| Gydan LNG |

Arctic coast |

planning |

16 |

2018-22 |

Novatek |

| Pechora LNG |

Arctic coast |

delayed |

10 |

NA |

Rosneft |

| Shtokman LNG |

Arctic coast |

delayed |

30 |

NA |

Gazprom |

| Regasification projects |

| Kaliningrad LNG |

Baltic coast |

planning |

2.4 |

2017 |

Gazprom |

| Source: U. S. Energy Information Administration based on Sakhalin Energy, Total, Novatek, Gazprom, Rosneft, Barents Observer, and World Gas Intelligence. |

Electricity

Russia is one of the top producers and consumers of electric power in the world, with more than 230 gigawatts of installed generation capacity. In 2012, electric power generation totaled approximately 1,012 billion kilowatthours, and Russia consumed about 889 billion kilowatthours.

Fossil fuels (oil, natural gas, and coal) are used to generate roughly 67% of Russia’s electricity, followed by nuclear (16%) and hydropower (16%). Most of the fossil fuel-fired generation comes from natural gas. Russia’s electric power generation totaled 1,012 billion kilowatthours (BkWh) in 2012, and net electricity consumption stood at 889 BkWh. Russia exported approximately 18 BkWh of electricity in 2013, mainly to Finland, Belarus, Lithuania, China, and Kazakhstan.65 Russia also imported almost 5 BkWh of electricity in 2013, mainly from Kazakhstan.

Sector organization

Much like the oil and natural gas sectors, a number of ministries and regulatory agencies are involved in the electric sector. The Ministry for Economic Development supervises tariffs and investment in the energy sector. The Ministry of Energy is in charge of general energy policy, including development of the legal framework for the electricity sector. The Ministry of Energy also approves investment plans for Russia’s electric transmission system.

The main regulatory agencies involved in the sector include the Federal Tariff Service (regulates transmission tariffs) and the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (oversees compliance with the unbundling rules and charges of abuse of market dominance in competitive electric markets). The state atomic energy corporation, Rosatom, controls all aspects of the nuclear sector in Russia including uranium mining, fuel production, nuclear plant engineering and construction, generation of nuclear power, and nuclear plant decommissioning.66

There are seven separate regional power systems in the Russian electricity sector. These systems are: Northwest, Center, South, Middle Volga, Urals, Siberia, and Far East. The Far East system is fragmented with a weak connection to its neighbor to the west, the Siberian system. The Siberian system is also weakly connected with its neighbor to the west, the Urals system. The remaining five systems covering European Russia are well integrated with one another and connected to systems in neighboring countries.67

The Russian electric sector was restructured in the past decade, and much of it was privatized. The reform required ownership unbundling in the electricity sector, separating the industry into largely privately-owned, competitive generation assets and state-controlled, regulated transmission assets. No company is allowed to own both generation and transmission assets. The Federal Grid Company, which is more than 70% owned by the Russian government (directly and through Gazprom), controls most of the transmission and distribution infrastructure in Russia. The grid comprises more than 1.5 million miles of power lines, including slightly less than 100,000 miles of high-voltage cables more than 220 kilovolts (Kv). The government has been trying to attract private investment into the wholesale and regional electric generating companies. As part of the market reform, most of Russia’s fossil-fueled power generation was also privatized, while nuclear and hydropower remain under state control.68

Nuclear power

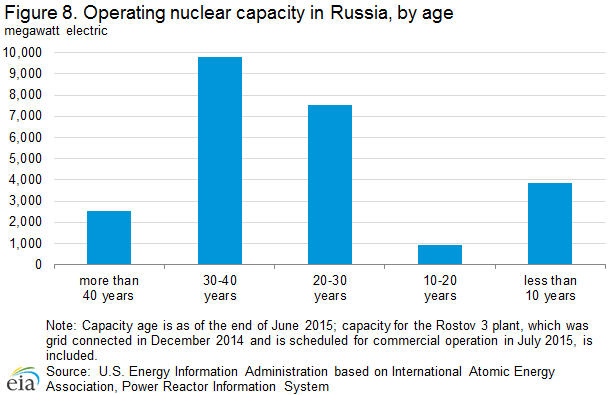

Russia has an installed nuclear capacity of more than 24 million kilowatts, distributed across 34 operating nuclear reactors at 10 locations. Nine plants are located west of the Ural Mountains. The only exception is the Bilibino plant in the far northeast.

Russia’s nuclear power facilities are aging. The working life of a reactor is considered to be 30 years, but Russia has an active life extension program. The period for extension is established by the government as 15 years, and 21 of Russia’s nuclear reactors, accounting for half of the country’s operating nuclear capacity, are 30 or more years old (Figure 8).69 Eleven of the country’s 34 nuclear reactors use the high-power channel reactor (RBMK) design employed in Ukraine’s Chernobyl plant.70 Russia’s newest reactor, the 1,011 Megawatt electric (MWe) Rostov 3 reactor, was connected to the grid in December 2014, and it is expected to begin commercial operation in the third quarter of 2015.71

Russia’s current federal target program envisions a 25% to 30% nuclear power share of total generation by 2030, 45% to 50% by 2050, and 70% to 80% by 2100. To achieve these goals, the rapidly aging nuclear reactor fleet in Russia will need to be replaced with new nuclear power plants. As of May 2015, nine new nuclear reactors were officially under construction across Russia, with 7,371 megawatt electric (MWe) net generating capacity. One of the plants under construction is a floating nuclear power plant, which is expected to commence operations by 2018.72

In addition to the nine nuclear reactors currently under construction, there are another 31 units planned, with a total gross generating capacity of more than 32,000 MWe. These units are planned to be completed between 2017 and 2030.![nuclear_operating]()

Coal

Russia has sizeable coal reserves and is the world’s third-largest exporter of coal.

With 173 billion short tons, Russia held the world’s second-largest recoverable coal reserves, behind the United States, which held roughly 259 billion short tons in 2011, the most recent year for which these data are available. Russia produced 392 million short tons in 2012, making it the sixth-largest coal producer in the world, behind China, United States, India, Indonesia, and Australia. About 80% of Russia’s coal production was steam coal, and about 20% was coking coal, according to Eastern Bloc Research.73

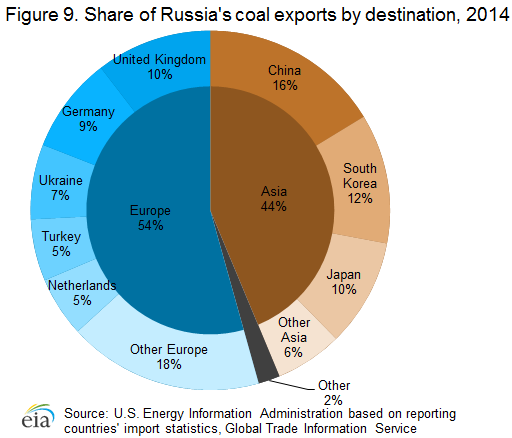

In 2012, Russia consumed a little more than three quarters of its coal production and exported the rest. Although coal accounts for a relatively modest share of Russia’s total energy consumption, it is a more vital part of consumption in Siberia, where most Russian coal is mined.

More than half of Russia’s coal production comes from the Kuzbass basin, in central Russia. Kuzbass coal must travel long distances by rail, about 2,600 miles to reach Russia’s Baltic port of Ust-Luga, for export to European countries. The overland distance to Voctochny port, for export to Asian consumers, is even greater.74 This long overland transport generally puts Russian coal at an economic disadvantage to competing sources of coal. Even so, in 2012, Russia was the third-largest coal exporting country in the world, exporting 145 million short tons, seaborne and overland. The top two coal exporters were Indonesia and Australia.

Russia’s coal exports have generally grown steadily since the late 1990s, with exports to Asia growing strongly in the past few years. In 2014, about 44% of Russia’s coal exports went to Asia (Figure 9).75 Russia’s total coal exports have almost tripled over the past decade. Exports are expected to continue to grow in the future. In the short-term, the weaker ruble, caused by sanctions and low oil prices, should make Russian coal exports more price-competitive in both Europe and Asia.

Russia’s coal-exporting ports are geographically located to serve either European or Asian markets. Some of Russia’s major coal ports include Murmansk, Ust-Luga, and Tuapse, all of which lie in the West and handle exports to Europe. Vanino and Vostochny lie in the East and handle exports to Asia.76 China and some East European countries receive imports from Russia directly by rail.77 Russia has plans to expand port capacity to facilitate more exports to Asia. Additionally, in late 2014 and early 2015, Russia delivered two test shipments of coal to the port of Rajin in North Korea, via a recently refurbished rail line. From Rajin, the coal was loaded on to ships for delivery to South Korea.78![by_destination]()

Endnotes:

1EIA estimates based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015, Data workbook, (accessed July 2, 2015) and Global Trade Information Service (subscription).

2International Atomic Energy Association, Power Reactor Information Service, accessed April 27, 2015.

3U.S. Department of State, Ukraine and Russia Sanctions, accessed April 13, 2015.

4“Announcement of Treasury Sanctions…” http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2572.aspx, accessed April 13, 2015.

5“Announcement of Expanded Treasury Sanctions…” http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/jl2629.aspx, accessed April 13, 2015.

6Henderson, James and Julia Loe, “The Prospects and Challenges for Arctic Oil Development,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (November 2014), p. 34.

7Oil & Gas Journal, “Worldwide Look at Reserves and Production,” (December 1, 2014) p. 32.

8Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, “Table 6 Production of oil+condensate by region, mn tons,” (2014), p. 2.

9Rosneft, Samotlorneftegaz and Yuganskneftegaz, accessed April, 27, 2015.

10Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, “Table 6 Production of oil+condensate by region, mn tons,” (2014), p. 2.

11Henderson, James, “Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (April 2015), pp. 4, 8.

12Tatneft, Oil and Gas Production, accessed April 28, 2015.

13Rosneft, Vankorneft, accessed April 28, 2015.

14Rosneft, Verkhnechonskneftegaz and East Siberian Oil and Gas Company, accessed April 28, 2015.

15Lukoil, Prospective Projects, accessed April 28, 2015.

16Exxon Neftegas Limited, Consortium members, accessed April 29, 2015.

17Exxon Neftegas Limited, Press Release “Sakhalin-1 Project Begins Production at Arkutun-Dagi Field,”(January 20, 2015).

18Shell, Sakhalin-2 – an overview, accessed April 29, 2015.

19Krysiek, Timothy Fenton, “Agreements from Another Era: Production Sharing Agreements in Putin’s Russia, 2000-2007,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (November 2007), pp. 19-26.

20Annenkova, Anna, “Russian Benchmarks of Black Gold,” Oil of Russia: Lukoil International Magazine, No. 4 (2012).

21ExxonMobil, About Sokol, accessed April 28, 2015.

22Nefte Compass, “Russia Exports New Crude Oil Grade,” (February 19, 2015), p. 3.

23Argus, Methodology and specifications guide: Argus crude, Asia-Pacific, Sudan, ESPO Blend, Sakhalin Island assessments (April 2015), p. 22.

24Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 7 (2014), pp. 3-5.

25Henderson, James, “Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (April 2015), pp. 4-7.

26BP, BP in Russia, accessed June 30, 2015.

27International Energy Agency, Russia 2014: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries (June 2014), pp. 20-22 and 192-193.

28Henderson, James, “Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (April 2015), pp. 36-48.

29Oil & Gas Journal, “Worldwide Refining Survey,” (December 1, 2014) p. 2.

30Rosneft, Oil Refining, accessed April 28, 2015.

31Lukoil, Oil Refining, accessed April 28, 2015.

32Henderson, James, “Key Determinants for the Future of Russian Oil Production and Exports,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (April 2015), pp. 44-46.

33Federal Customs Service of Russia and reporting countries’ import statistics, Global Trade Information Service (subscription).

34EIA estimate based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015, Data workbook, (accessed July 2, 2015) and Global Trade Information Service (subscription).

35Federal Customs Service of Russia and reporting countries’ import statistics, Global Trade Information Service (subscription).

36Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 134 (2014), p. 41.

37Table 3: Transneft, Projects; Sakhalin Energy, TransSakhalin pipeline system; Caspian Pipeline Consortium, General information; State Oil Company of the Azerbaijan Republic (SOCAR), Baku-Novorossisyk oil pipeline; Orlen Lietuva, Terminal and pipelines; European Parliament, Gas and Oil Pipelines in Europe, “Pipelines from third countries,” (November 2009) p. 11; Nefte Compass, “Transneft Seeks to Offset Upstream Delays,” (April 16, 2015) p. 5; and Rodova, Nadia, “Capacity crunch threatens Russia’s ESPO oil exports,” Platt’s Oilgram Price Report, (February 4, 2015) pp. 1, 34.

38Lloyd’s List Intelligence (APEX tanker data).

39Lenmorniiproekt, Oil loading port Primorsk, accessed April 28, 2015.

40Ust-Luga Company, Complex of bulk cargoes, accessed April 28, 2015.

41Kommersant, “New Terminal Project in the port of Novorossiysk…,” accessed April 28, 2015.

42Transneft Kozmino Port, About the Company, accessed April 28, 2015.

43Platt’s Oilgram Price Report, “Capacity crunch threatens Russia’s ESPO oil exports,” (February 5, 2015), p. 1.

44Tamaneftegas, Project outline, accessed April 28, 2015.

45PortNews, “Throughput of Tamanneftegas totaled 5 mln t in Jan-Sep’14,” (October 15, 2014).

46Sibur, “First gas carrier loaded at the new LPG transhipment terminal in Northwest Russia,” accessed April 28, 2015.

47PR Newswire, “NOVATEK Completes Construction Of The Second Stage Of Ust-luga Complex,” (October 16, 2013).

48Chemicals Technology News, “SIBUR commences propylene production using UOP technology at Russian plant,” (December 18, 2014).

49Sibur, “SIBUR proceeds with ZapSibNeftekhim project,” (September 16, 2014).

50Oil & Gas Journal, “Worldwide Look at Reserves and Production,” (December 1, 2014), p. 32.

51Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 34 (2014), p. 14.

52International Energy Agency, Russia 2014: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries (June 2014), pp. 20-22 and 192-193.

53Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 33 (2014), p. 14.

54National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Estimated Flared Volumes from Satellite Data.

55BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015, Data workbook, (accessed July 2, 2015).

56Gazprom, Transmission, accessed July 1, 2015.

57Table 7: Gazprom, Gas pipelines; GazpromExport, Transportation and Projects; Sakhalin Energy, TransSakhalin pipeline system; World Gas Intelligence, “Gazprom Braces for Yet More Pain,” (January 7, 2015), pp. 2-3; Nefte Compass, “Gazprom Defeats Rosneft in Sakhalin Dispute,” (February 26, 2015), p. 4; RT, “Putin breaks ground on Russia-China gas pipeline, world’s biggest,” (September 1, 2014); and Reuters, “Russia’s Gazprom says no delays in gas deliveries to China,” (April 6, 2015).

58Yafimava, Katja, “Evolution of gas pipeline regulation in Russia: Third party access, capacity allocation and transportation tariffs,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (March 2015).

59Yafimava, Katja, “Evolution of gas pipeline regulation in Russia: Third party access, capacity allocation and transportation tariffs,” Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, (March 2015), pp. 16-17.

60World Gas Intelligence, “Gazprom and Rosneft Still at Loggerheads,” (March 18, 2015), p. 3.

61World Gas Intelligence, “Russia’s New Asian Ambitions,” (March 30, 2011), pp. 1-2.

62BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2015, Data workbook, “Natural Gas: Trade movements 2014 as liquefied natural gas”(accessed July 2, 2015).

63Table 8: Sakhalin Energy, Prigorodnoye production complex; Total, Yamal LNG; Novatek, South-Tambeyskoye Field (Yamal LNG Project); Gazprom, Baltic LNG; Gazprom, Vladivostok LNG; Rosneft, Gas Strategy; Staalesen, Atle, “Novatek plans second LNG plant in Arctic,” Barents Observer (January 30, 2014); and World Gas Intelligence, “Sanctions, Prices Hit Russian LNG Plans,” (April 8, 2015), pp. 3-4.

64Novatek, South-Tambeyskoye Field (Yamal LNG Project), accessed April 27, 2015.

65International Energy Agency, Russia 2014: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries (June 2014), p. 185-187.

66International Energy Agency, Russia 2014: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries (June 2014), pp. 20-22 and 192-193.

67Belobrov, Vladimir, Electricity Markets in Russia, accessed April 27, 2015.

68International Energy Agency, Russia 2014: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries (June 2014), pp. 183 and 198.

69International Atomic Energy Association, Power Reactor Information Service, accessed April 27, 2015.

70World Nuclear Association, RBMK Reactors, accessed April 26, 2015.

71World Nuclear Association, Nuclear Power in Russia, accessed April 27, 2015.

72World Nuclear Association, Nuclear Power in Russia, accessed April 27, 2015.

73Eastern Bloc Research, CIS and East European Energy Databook 2014, Table 39 (2014), p. 16.

74Carbo One, Logistics, accessed April 27, 2015.

75Reporting countries’ import statistics, Global Trade Information Service (subscription).

76Suek AG, Seaborne Deliveries, accessed April 24, 2015.

77Suek AG, Railway Deliveries, accessed April 24, 2015.

78Kwaak, Jeyup, “South Korea Prepares for Coal Shipment From North Port,” The Wall Street Journal, (November 28, 2014), accessed April 24, 2015 and Byrne, Leo, “Second batch of Russian coal sent south from N.Korea,” NK News, (April 16, 2015), accessed April 24, 2015.